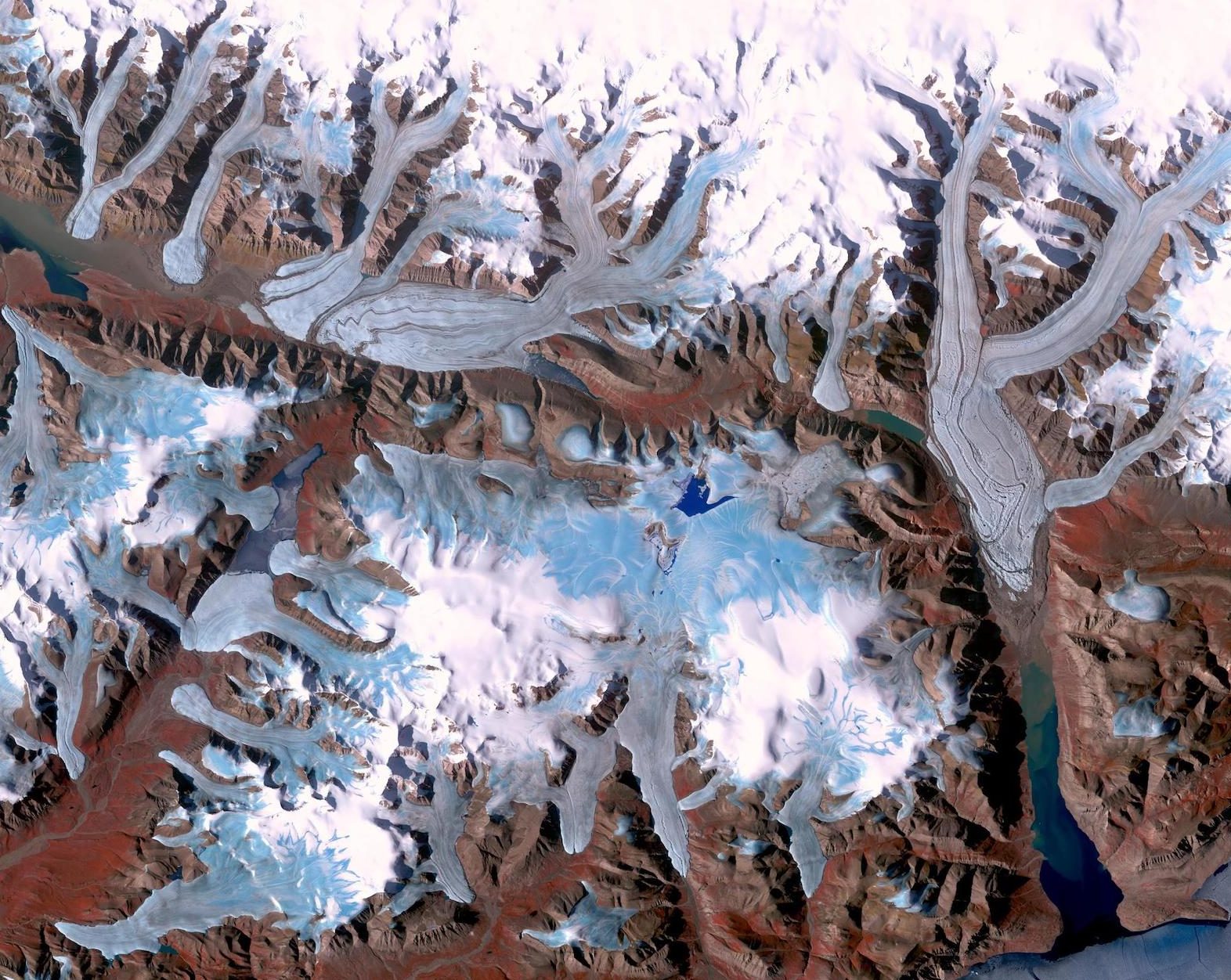

Last July, glaciologist Derek Mueller made his fourteenth yearly quest to gather samples from Milne Fjord, a research station on the coastal margin of the “Last Ice Area”— a 400,000-square-mile region north of Greenland and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The facility sits well-nigh 500 miles from the North Pole, nestled between tremendous ice flows. The landscape is rich with harsh beauty: Melt ponds, underlined by glistening ice, rest between white hillocks. Contrasted versus the vivid white ice and dark, churning sea, each pool glows with its own crystal-blue light.

Mueller’s work had focused on Milne Fjord’s only known epishelf lake — a microbially rich ecosystem that arises when an ice shelf creates a dam, permitting a thin layer of freshwater to bladder whilom seawater unfluctuating to the unshut ocean. As with the rest of the Arctic, they are threatened by climate change. But there was reason to hope for Milne Fjord: For years, scientists believed this area, home to the oldest and thickest ice in the northern hemisphere, would survive the worst effects of global warming.

But as Mueller and his team approached their old testing grounds, they could tell something was amiss. Where there had once been fingers of turquoise, there was now only the vivid white of ice and the ghostly remnants of melt water.

Milne Fjord’s epishelf lake had all but disappeared.

“It’s a mixed bag of emotions,” said Mueller. “There’s the scientific marvel of measuring a waffly system, but at the same time it’s a feeling of unconfined loss.”

The Arctic is no stranger to depletion, warming at a rate nearly four times faster than the rest of the planet. It’s widely known that as glaciers calve and collapse, ice-dependent habitats and the wildlife that depend on them will protract to disappear. But while famished polar bears, retreating ice, and warmed-over viruses tend to momentum headlines well-nigh Arctic thaw, the slow but steady thaw of the Last Ice Zone places scientists on a new level of alert.

Not only does its disappearance sound an unexpected warning tintinnabulate for climate transpiration and the stat cycle, it moreover ways there may be little time left to learn from the Arctic’s unique ecosystems — surpassing they disappear.

The Last Ice Zone was once so frozen and hostile it stymied those who sought to traverse it. In the summer 1875, British explorer Albert Hastings Markham wrote of Milne Fjord:

A mannerly day, although the temperature persists in remaining minus 30 degrees [C]. Glare from the sun has been very oppressive; the snow in places resembles woody sand, and appears increasingly crystallized than usual. A few of the party, including Parr and myself, suffering from snow-blindness. Distance marched ten miles…a unconfined expanse of hummocks varying in height from twenty feet to small round nobly pieces over which we stagger and fall…There is no endangerment at present to get out, as the ice pack is too thick.

The ice shelf was so rugged, in fact, that the team was forced to turn back. But, nearly 148 years later, the Arctic bears little resemblance to that description. According to NASA, the extent of summer sea ice — the zone in which satellite sensors show to be at least 15 percent covered in frozen water — is shrinking by increasingly than 12 percent per decade.

Satellite observations have shown that between 1997 and 2017 alone, the region lost virtually 31 trillion tons of ice. Even if we do manage to limit global warming to the goal of 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F), a recent study predicted the Earth would still lose a quarter of its glacier mass.

There are myriad reasons why the Arctic is warming so quickly (a miracle scientists often refer to as Arctic amplification), but a leading culprit is sea ice melt. The Arctic’s sea ice, typically 3 to 15 feet thick, freezes during winter and melts each summer. The white, snow-covered sheets reflect roughly 85 percent of incoming solar radiation when out to space. The unshut ocean, on which the ice floats, is so visionless that it absorbs 90 percent of it.

As the region’s sea ice melts, solar traction rates create a positive feedback loop: The warmer the ocean, the less ice. The less ice, the increasingly heat is absorbed. The increasingly heat, the warmer the ocean.

Even written for this cycle, most climate models predicted the Last Ice Zone would remain relatively frozen, vicarial as a seasonal stronghold for ice-dependent animals. In the summer ice flows from continental ice shelves near Siberia tend to pile up in the area, forming frozen ridges increasingly than 30 feet high.

But it seems Milne Fjord’s thick ice isn’t unbearable to shield it from the current pace of warming. “The glaciers melting are bringing freshwater down, subtracting heat into the fjord and the epishelf lake,” Mueller said. “Having weaker ice in the fjord would midpoint that the glacier could whop faster, thin out faster, and unravel up faster. ”

While it’s too early to determine the word-for-word rationalization overdue the disappearance of Milne Fjord’s epishelf lake, Mueller thinks that drainage may be attributed to the Milne Ice Shelf breaking untied two years ago. In 2002, scientists observed a similar phenomenon when the Ward Hunt ice shelf tapped off, causing the Disraeli Djord Epishelf Lake to phlebotomize away.

“We’re really seeing the last death row of these epishelf lakes,” he said. “There aren’t any others in Canada as far as we know.”

It’s not just epishelf lakes that are disappearing from the Far North. Researchers sometimes refer to Arctic lakes as “sentinels,” due to their swift responses to shifting conditions. “Lakes are increasingly sensitive than other ecosystems to climate change,” said environmental microbiologist Mary Thaler, who felt compelled to study the Arctic’s ecosystems considering of the dwindling time they might remain in existence. “They’re like the warning tintinnabulate going off, the first ones to take the hit, and we see them stuff utterly transformed.”

According to a 2022 study, lakes constitute scrutinizingly 40 percent of the Arctic lowlands, the largest surface water fraction of any terrestrial biome. In wing to providing crucial habitat for upper Arctic wildlife, marine species, and migratory birds, they are a hair-trigger source of freshwater for Indigenous communities such as the Komi and Nenets.

The rapid disappearance of these essential persons of water has surprised some researchers. Scientists once predicted that climate transpiration would initially expand them wideness the tundra. Although they knew drainage might sooner occur, it wasn’t expected for a few hundred increasingly years. But it seems that the thawing of underlying permafrost, the frozen mixture of soil and organic matter that blankets the far north, is counteracting the expansion effect.

Permafrost is an important form of long-term storage for stat — holding nearly twice as much as currently found in the atmosphere. But that worthiness depends on permafrost remaining frozen. As the ground thaws, plants or animals veiled within can resume decomposing, releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Permafrost, particularly the layers under Arctic lakes, can moreover contain a particularly upper number of frozen microbes, which help facilitate the release of gases. While a few scientists have expressed concerns over the re-release of prehistoric diseases and pathogens, most researchers say the real worry has to do with climate feedback loops.

“The important part is that it is a very large reservoir of stat that we don’t want moved into the atmosphere,” said Arctic ecologist Elizabeth Webb.

Webb’s research has largely focused on why Arctic lakes are disappearing far increasingly quickly than expected. She found that the decreases in surface water over the last 20 years have been correlated with two unshared climate variables. The first, not surprisingly, is increasing temperatures. The second and far increasingly puzzling factor to researchers is the climate-driven increase in rainfall.

It may seem counterintuitive that increasingly rain could lead to fewer lakes. “We were like, why in what world does this make sense?” Webb said. But considering autumnal rain is warmer than the frozen ground, it brings a whole lot of heat to the underlying permafrost. That warmth can unshut up underground channels that phlebotomize surface water.

“This drying of lakes was expected,” says Webb, “but it’s happening way older than the models projected.”

But time is short to icon out what it all ways for the Arctic and beyond. Researchers in the zone lost two years of fieldwork due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and many projects were remoter elapsed by the proposal reservoir for trek funding. Even the unpredictable Arctic weather can turn versus scientists, with unrepealable expeditions requiring well-spoken skies in order for helicopters to take scientists to key sample sites. Mueller remembers an trek where fog and rain elapsed his team’s inrush by 10 days. “By the time we unquestionably got there, we basically got the yellowish minimum of what we needed done,” he said.

For those lucky unbearable to have procured samples from the disappearing ecosystems of the Arctic, those materials have taken on a new significance.

In Quebec City, Thaler analyzes small amounts of freshwater drawn during a 2016 excursion to Milne Fjord’s epishelf lake. The lake is no more, but the samples teem with life. Thaler goes through each one, trapping bacteria, viruses, and other microbial DNA in filters.

“We had looked at other parts of the Milne Epishelf Lake’s ecosystem but never the viruses,” she said. “Because it’s so dark, cold, and poor in nutrients, most of what’s in the lake is tiny microscopic life — so viruses can make huge differences in which species are going to thrive.

Thaler and her team found that in terms of viruses, the lake had been 25 percent increasingly well-healed and diverse compared to the marine layer beneath.

“Everything that is going on in terms of photosynthesis, respiration, and releasing stat is unquestionably stuff driven by this microscopic community,” she said. “We wanted to know, are there species or genetic codes or variegated traits that are only found in this one lake? Now, anything that was unique or special well-nigh it has been lost forever.”

Much like the periodical entries from 1875, the lake’s samples offer a glimpse into the ecosystems of the past – a historic snapshot of a yesterday world. For his part, Mueller thinks when on his work at Milne Fjord with a feeling of winds and urgency — but moreover hope.

“It’s an environment that is stunningly trappy and rather unique. It would be nice to fully typify it and understand it surpassing it’s lost forever,” he said. “There’s no local solution to any of this – it’s a global problem, so we need global changes to write this.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline The ‘Last Ice Area’ is once disappearing on Feb 10, 2023.